For Mary Swann, the real country has more grit than a spaghetti western.

For Mary Swann, the real country has more grit than a spaghetti western.

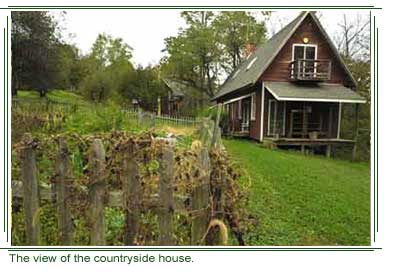

Moving out to the boonies in 1968 came with dirt, hard work, and wide-open spaces. Living in the country meant doing without conveniences. As Mary would say, it was real. “As a kid, I always wanted to live in the real country. I had grown up in Long Island after most of the battles with development had been lost,” said Mary.

When Mary and her first husband, Mark, bought their farm, they were seeking a lifestyle closer to the natural cycle. They wanted their children to know where their food came from, and to grow with the outdoors as their playground, their toys the soil and the creek. Year after year, their small farmhouse and 167 acres became more comfortable. The Swann family raised pigs and slaughtered them in the fall, gave peach parties in the summer, and chopped wood for the winter. The children grew up and moved on. Eventually Mark moved on too. Mary remarried.

Mary’s second husband, Josh Brumfield, grew up in rural Maryland. There, he watched as his childhood farm succumbed to growth. Southern York County reminded him of the life that he had lost. “Ever since I first came to this area, I loved the countryside — its wildness and the creek,” Josh said.

A Crisis

In 1997, life changed for Mary and Josh. While walking along a hillside they found something disturbing: bright orange surveyor flags on their neighbor’s farm. Josh wasn’t entirely surprised; he had been anxiously watching as farms turned into housing tracts and shopping centers were erected amidst dilapidated farm buildings. But the couple knew their neighbor and always thought they would get first chance if he should want to sell the farm. Now it was too late.

The proposed development called for 55 houses. The thought of the ground being stripped upset them. The knowledge that 55 families would be drawing ground water in a community that has seen many dry wells worried them. And they fretted over the impact construction and pavement would have on Muddy Creek, a high-quality trout stream. Josh became a regular at township meetings and encouraged others to attend. Over time, the community’s demand for answers was too much for the developer. He offered to sell the property to Josh and Mary.

They knew to save the land they would have to act quickly. Mary owned a 244-acre woodland, which she had purchased along with the farm in 1968. The couple used it as collateral to buy the farm. It was a short-term solution. After pooling together the family savings, Mary and Josh found that they could last two years paying the mortgage on the new land before they ran out of money.

They now owned three properties: the 167-acre farmstead where they lived, the new 203-acre farm, and the woodland. But they didn’t have the means to keep these lands protected. “We had more land than we needed or could afford,” Mary said. “I never wanted to own a lot of land, but I couldn’t bear to see it desecrated.”

First Try: Conserve the Farm

The couple heard about farmers in the area selling conservation easements — giving up their development rights — on their farms to the county agricultural land preservation board. They applied to the board, hoping to get enough money to pay down some of their very large mortgage. They were turned down.

Second Try: Conserve the Woodland

Mary and Josh then turned to the Farm and Natural Lands Trust of York County. They were looking to donate a conservation easement on Mary’s woodland. The woodland is a special place with wetlands and mature trees. Wildlife is plentiful. Muddy Creek, a well-known coldwater fishery, winds its way through the property. As rumors of conservation circulated in the sportsman community, the Farm and Natural Lands Trust received inquiries from fly fishers about the property’s accessibility. By donating a conservation easement, Mary and Josh hoped to accomplish two things: protect the woodland should they sell it and get a big tax deduction to pay down the mortgage on the new farm.

In removing the woodland’s development potential, the easement would reduce the property value. Since protecting the woodland would be in the public interest, Mary and Josh could receive a charitable deduction on their federal income taxes equal to the reduction in the property’s value. Unfortunately, it turned out the tax deduction was nowhere near big enough to help with their debt.

The couple was back where they started, and their savings were going fast.

Third Try: Conserve it All

Jackie Kramer of the Farm and Natural Lands Trust recognized the woodland’s great natural values and continued to look for a way to protect it. Likewise, Patty McCandless, York County’s farmland preservation coordinator, saw that Mary and Josh had some great farmland and wanted to help them find a way to conserve it. While Jackie and Patty were working on the problem, the Pennsylvania Game Commission was looking at land in York County. The Commission was interested in purchasing and adding Mary’s woodland to its statewide system of public hunting grounds. However, the Commission is limited in how much of its money it can spend to buy land and needed to partner with a land trust to raise capital. The Commission called Jackie.

Jackie didn’t know what could be done but felt that the Game Commission, the farmland preservation program, and the land trust should sit down together with the couple to discuss their situation.

They met in Mary and Josh’s kitchen.

“For the first hour, we considered each property separately,” recalls Jackie. “We were crunching the numbers and couldn’t see a way to conserve even one property.” Then Jackie suggested that they view things as one big 600-acre conservation project. The change of perspective was like a flip of a switch. Suddenly, there were possibilities. Jackie jokes, “Three meetings and twelve hours later we figured it out.”

The solution would result in the conservation of all three properties, the sale of the woodland, and enough money for Mary and Josh to pay off the mortgage. First they looked at the farmland preservation program with new eyes. The county program requires that 50 percent of the property be in agricultural production. By applying this rule to the homestead and the new farm as one property, as was originally done, Mary and Josh didn’t qualify.

Patty and Jackie suggested they only submit the new farm to the program. That farm had been worked for years and had more than enough acreage to qualify. The preservation program subsequently accepted the farm. Mary and Josh still wanted to protect their homestead property, so they looked at donating a conservation easement on that 167 acres to the Farm and Natural Lands Trust. In an ironic twist, recent development in their area had caused land values to increase, and in turn, the potential tax deduction for donating an easement.

Using the easement sale proceeds and their easement donation tax benefits, Mary and Josh were able to pay down their mortgage, releasing the lien on their woodland property. The woodland was appraised at $305,000, but the Game Commission was only approved to pay $97,000 for the property. The Farm and Natural Lands Trust set out to purchase the property and then resell to the Commission at a steep discount.

The Trust secured a $100,000 grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) Keystone Fund to help buy the land. Mary and Josh agreed to sell the land to the Trust for $200,000, donating $105,000 of the land’s value. “They were only able to donate the land value because the county program paid for the farm easement,” said Jackie. “Without the one, the other couldn’t happen.” After buying the woodland for $200,000, the Farm and Natural Lands Trust resold it to the Game Commission for $97,000. The land is now part of State Game Land #327.

Mary and Josh are happy with the results. What began as a crisis purchase to save one farm led to the permanent protection of 600 acres. The couple donated more than $200,000 in land and development rights — money they could have pocketed. But for them, the return on their investment is priceless.

Mary explained, “We were able to conserve and pay off the mortgage on the farm next door and dedicate some of our home woods and creek frontage to the Trust. And we are assured that the woodland, which provides a home to rare and endangered species, will be a source of enjoyment and wonder for generations to come.”