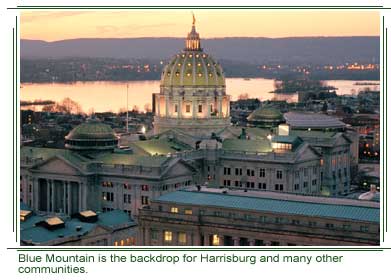

No artist could have painted a bluer sky or puffier clouds the day Carol Witzemen stood on Blue Mountain.

Under that perfect sky, the Witmer estate was being sold. Cargo vans and pickups were parked in rows like church pews dropped in the meadow. The crowd followed the auctioneer as he skittered between pockets of old furniture, antiques, and mounds of dusty books, chanting a lifetime’s accumulation of stuff away.

Under that perfect sky, the Witmer estate was being sold. Cargo vans and pickups were parked in rows like church pews dropped in the meadow. The crowd followed the auctioneer as he skittered between pockets of old furniture, antiques, and mounds of dusty books, chanting a lifetime’s accumulation of stuff away.

Carol tapped her foot impatiently. She wasn’t interested in the box lots, lamps, and furniture up for auction. Carol had her eye on buying the top of the mountain.

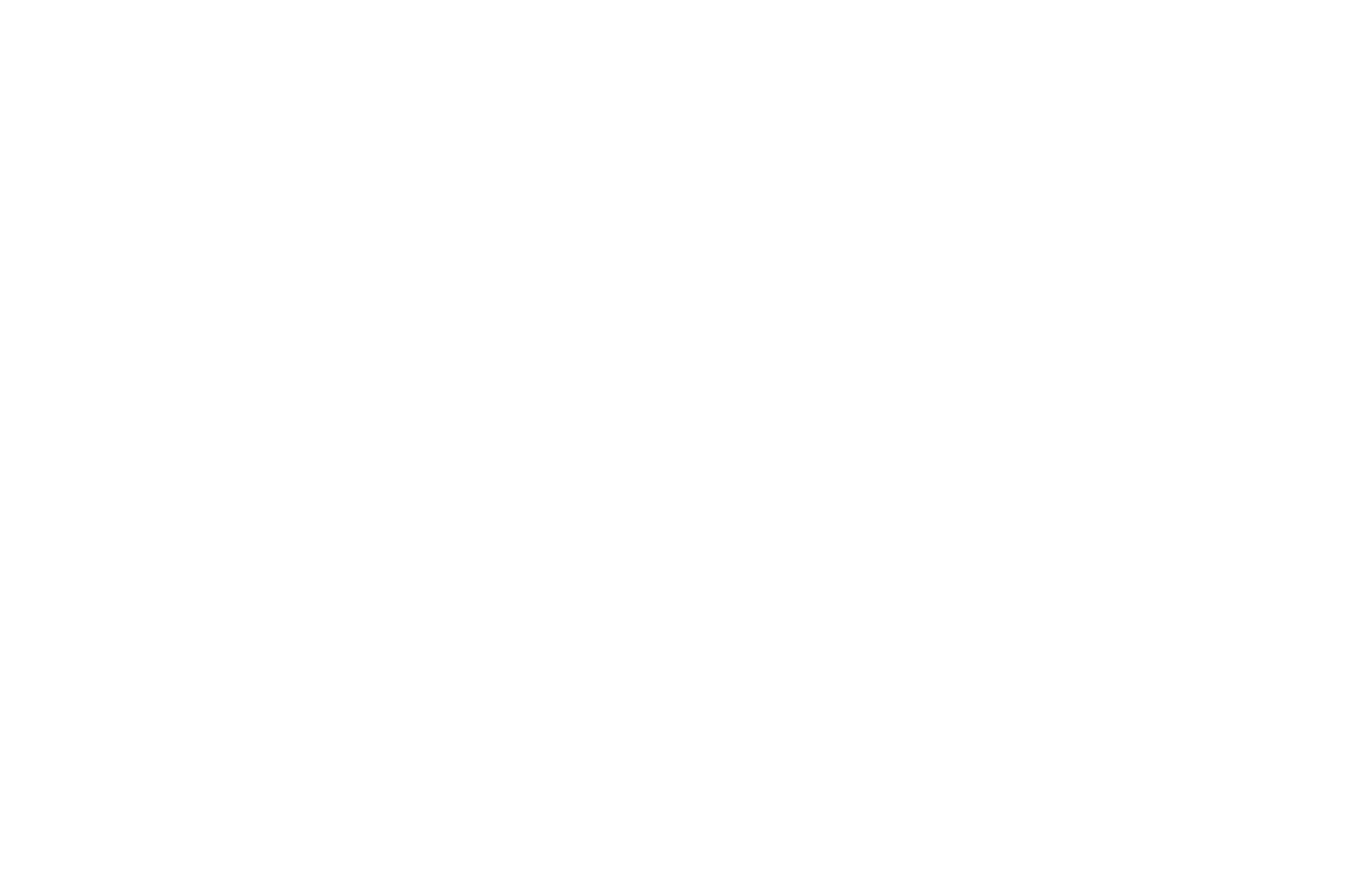

Carol was the president of the Central Pennsylvania Conservancy, a charitable organization that conserves special places by buying them. Blue Mountain is one of those special places. Blue Mountain stretches over 200 miles from northern New Jersey down through 11 Pennsylvania counties to the Maryland state line. The mountain is also known as First Front Mountain and the Kittatinny Ridge. For hundreds of communities it provides scenic beauty, hunting, and fishing. It also hosts the world famous Appalachian Trail.

The ridge provides the headwaters for many of the streams in south central and southeast Pennsylvania, supplying clean freshwater habitat for fish and water for people. Rain and melting snow on the mountain drain into 1,597 sources of public drinking water. The mountain’s forests provide some of the best wildlife habitat in the state, and the ridge has worldwide significance as a flyway for hawks, eagles and songbirds. Thousands of people climb onto high outcroppings to view the mass migration at Hawk Mountain and other good viewing spots. The Audubon Society has named it an Important Bird Area.

The Witmer estate is a small part of the ridge but an important link to the whole. It is also the first Blue Mountain property the Central Pennsylvania Conservancy set out to save.

The Auction

It was past noon when the auctioneer turned from house wares to the land. Carol and another Conservancy volunteer, Craig Dunn, squinted in the bright sun. From the Witmer farm’s high perch, they could see the entire Cumberland Valley. They knew that the view, the wooded lot and the relatively short commute to Harrisburg would attract a crowd. They also knew that the Conservancy’s volunteer board had authorized them to spend no more than $175,000.

The bidding began.

Carol jumped in at $50,000, then $60,000 and up to $70,000 before her competition dropped out. For a joyous moment, nothing could be heard but a passing crow. Just as the word “bargain” formed in Carol’s mind, two more bidders revived the din. Within seconds the dream was dashed and the Conservancy’s $175,000 limit was reached.

“Something told me that the other bidder was under the same instructions as I was,” Carol said. “And I wasn’t going to lose it for $500.” Carol made the winning bid of $175,500; the board forgave her the extra $500.

Witmer was only the first of the Conservancy’s Blue Mountain projects. Over three years, the land trust spent more than a half million dollars on three pieces of Blue Mountain land. The organization financed each purchase with a mortgage, counting on the many people who love the mountain to help pay off the debt. Private groups with diverse interests answered the Conservancy’s call for contributions. Local residents rallied as well, knowing the land would forever be open to the public. Hunters were well represented, with support from groups such as the Blue Mountain Chapter of the Safari Club International, the Ruffed Grouse Society, the Pennsylvania Falconry and Hawk Trust, the Susquehanna Water Fowlers Association and the Pennsylvania chapter of the National Wild Turkey Federation.

“I’m 56 years old and I’ve been hunting over there since 1968,” said Don Heckman, executive officer of the Pennsylvania Chapter of the Wild Turkey Federation. “One of the best ways to ensure conservation of special lands is to buy them when they become available and add them onto the state forests and game lands.”

The Audubon Society, the Keystone Trails Association, and the Susquehanna Appalachian Trail Club joined the hunting groups in contributing funds. Because of the benefits to the public, the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources granted Keystone Fund* money to the conservation effort. Also supporting were the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development and several local municipal and county governments.

One Down…

A year after purchasing the Witmer tract, the mortgage was paid. Carol once again stood on the mountain, holding the mortgage in one hand and a lighter in the other. All cheered as flame and paper met. Not long after burning the Witmer mortgage, the Conservancy burned the mortgage on its second acquisition, the Lightner property. And not long after that, the Conservancy purchased its third property, dubbed Blue Mountain East. “We’re still holding the mortgage on Blue Mountain East,” Carol said. “But what is the value of a public view of all of Cumberland Valley? What is the value of important wildlife habitat and bird migration flyways? Likewise, what is the value of the Appalachian Trail?”

John Plowman, a retired Game Commission employee, has lived in the area all of his life. “Every week there’s a new road being cut up the mountain,” said John. “I never thought the mountain would be covered with houses. You just didn’t build there; it was sacrosanct.”

Making Connections

Keeping a core of undeveloped forest along the Kittatinny Ridge is crucial to wildlife and water quality and important to public recreation. Protecting that core presents a challenge. Although some of Blue Mountain has been conserved, most of it is unprotected.

Central Pennsylvania Conservancy is part of the Kittatinny Ridge Coalition, an alliance of sportsmen, conservation groups, businesses, landowners, government, and tourism agencies. The Coalition seeks to raise public awareness of the importance of the ridge — and each little part of it — to wildlife and people. Ridge Coalition members meet, pore over maps and reach out to communities. Carol, while an enthusiastic participant, would prefer to be on the mountain.

“I hate meetings,” she said. “I’d rather be out buying land.”

Bob Lightner’s great grandfather was a Hessian. He emigrated from Germany to fight the Revolutionary War, but he forgot about battle when he fell in love with the Pennsylvania landscape. “He saw the land and said ‘this place is great. I think I’ll stay — the heck with the war,” Bob said. “He bought land at the foot of Blue Mountain and my family has never left.” For more than 200 years the Lightner brothers, sisters, sons and daughters farmed here. George and Dotty Lightner, Bob’s parents wouldn’t consider selling the land, not even a sliver. “After my father died, people would ask mom if they could buy just a small piece of our land, ” Bob said. “Mom would say, ‘It’s not my land to sell. That’s for the deer and other animals.”

Bob shared his mother’s feelings. When he read a newspaper article about the Central Pennsylvania Conservancy’s Witmer project — just up the road from his property — he talked to his sisters about selling at a discount to the Conservancy.

Thanks to the family’s generosity, the Lightner tract became the Conservancy’s second project on Blue Mountain.

Thanks to the family’s generosity, the Lightner tract became the Conservancy’s second project on Blue Mountain.

“I had a good life,” Bob said. “The Valley gave me a lot. I would like to give it something back.”