Dead Man’s Hollow Wildlife Preserve, 400 acres of protected forest and streams, provides peace and quiet to its visitors. Factories, strip malls, roads, and traffic seem a world away.

Dead Man’s Hollow Wildlife Preserve, 400 acres of protected forest and streams, provides peace and quiet to its visitors. Factories, strip malls, roads, and traffic seem a world away.

People walk the trails and absorb the surroundings even as a cool November rain falls. The steel-gray sky provides a backdrop for the brilliant yellow of slowly fading sycamore trees.

One hiker pauses, leaning on his well-worn walking stick, before using it to whack a clump of plants.

“This is Japanese knotweed,” David Pencoske explains. “It isn’t native to Pennsylvania and it crowds out plants that belong here.”

Pencoske, a native of nearby White Oak, is a volunteer steward of the land. He spends his free time hiking, scouting out non-native plants and uprooting as many as one man can.

“I spend so much time in the Hollow,” Pencoske says. “The mountains in White Oak where I live were all lumbered off and roads and buildings were put up. Everything is developed.”

Until recently, Dead Man’s Hollow could have been developed as well. However, Allegheny Land Trust (ALT), a regional land conservation organization, worked diligently to permanently secure this peaceful green space. They succeeded and now own and manage the Hollow as a wildlife preserve.

The sights, sounds, and activities of civilization surround but seldom intrude into the Hollow. The modest homes of Lincoln and Liberty Boroughs border much of the wildlife preserve. A hundred yards away, just across the Youghiogheny River, sits McKeesport. Having lost half its population since the decline of Big Steel, the city deals with challenges common to small cities throughout the northeastern states. A mile away in the opposite direction, U.S Steel’s Clairton Coke Works converts 18,000 tons of coal into coke for steel production each day. The largest coke operation in the United States, the massive facility dominates three miles of riverfront.

At one time the Hollow was an industrial center. It was the site of a 19th century quarry and an early 20th century factory. Until the late 1920’s, the Union Sewer Pipe Company manufactured clay sewer pipes there. The operation supplied almost all the cities of Pennsylvania, New York, and New England. If one could spy into those years from the tops of today’s tall trees, the view would be dominated by acres of flattened muddy storage yards, huge coal-fired kilns, rails, and roads. However, with the pipe company’s end came a new beginning. The site became the play yard of children. For some, it became a place to dump garbage; for others, a place to hunt. And as the decades passed, a forest grew.

When ALT announced its intention to conserve the land at Dead Man’s Hollow in 1995, Pencoske was skeptical. The Hollow was less than pristine, not what most people considered worth saving. He was so intrigued that he volunteered to help clean up the Hollow.

The Land Trust

The Land Trust

In 1994, the Allegheny County Natural Heritage Inventory, a study commissioned by the County of Allegheny, identified Dead Man’s Hollow as one of the most significant unprotected natural areas in the county. Like the rest of this urban county, the Hollow had been logged and used for other industry. However, its lack of roads and utility lines made it unique.

ALT reviewed the study, which concluded that there was little protected open space in the area and identified a stretch of riverfront in the Hollow that would likely be needed for the planned 152-mile Great Allegheny Passage trail. After considering these factors, ALT decided to make conserving the Hollow its top priority. The organization reached out to the private landowners and initiated negotiations to purchase the largest parcels comprising the Hollow.

By 1998, the land trust had purchased and permanently protected 396 acres–the better part of this wooded stream valley. The purchases were funded through grants from the County of Allegheny, the Keystone Fund, and the Katherine Mabis McKenna Foundation, with the support of many individuals and businesses. In 1999, the Buchanan and Flowers families donated their four acres in memory of family members.

“We were happy to make a gift that will benefit people and wildlife today and 100 years from now,” Robert Buchanan said at the time.

ALT now manages the Hollow as a wild place and provides recreational and educational opportunities for the public.

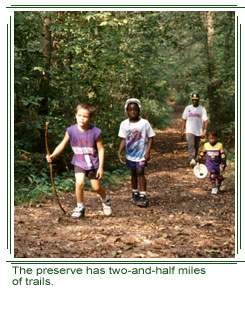

“We built two-and-half miles of trails. And we cleared out twenty tons of old tires and trash. U.S. Steel workers and local supporters helped make it all happen,” says Bill Lawrence, an ALT board member who participated in the original decision to pursue the conservation of the Hollow.

Lawrence drives the hour from his apartment to hike the trails and enjoy the Hollow’s tranquility. He knows where the largest tree stands and how the factory pipe discards in the streambed absorb enough water to keep the ground wet in drought years.

“All kinds of people like it here,” Bill says. “Because of the benches that were built by U.S. Steel workers, we have people with walkers who use the trails.”

A Family Treasure

The benches provided welcome rest for Alana Redenbaugh and her father, John Kiser. When doctors advised her aging father to get more exercise, Alana brought him to the Hollow, partly because it is a short walk from her home but mostly because she loves the place. John has since died, but the times Alana and her three children spent with him in the cool quiet of the trails are precious memories.

“It was a nice place to walk,” Alana said, recalling her days with dad. “He used to talk about the pipe factory that was here when he was a boy. I wouldn’t know anything about this place if it weren’t for him.”

John ran through the Hollow as a child, using it like generations of area children. The mysterious woods were a giant playground and offered an escape from the watchful eyes of adults. Today the Hollow is his grandkids’ playground. It is also their school–Alana home-schools her children and the Hollow lends itself to many lessons. In spring, Timothy, Katie, and Nicholas study the emerging life of the season. Warmer weather invites the family to sit under a tree to chat and read good books. Winter fun is looking for animal tracks in the snow.

“It really helps the kids to visualize life without houses around,” Alana said. “We’ve taken books to the Hollow to read one or two chapters on pioneers.”

For a biology lesson, the children watch salamanders move about the muddy ground, record their whereabouts, and measure them.

For a biology lesson, the children watch salamanders move about the muddy ground, record their whereabouts, and measure them.

“I try to go down there as much as I can,” Timmy says. “We found salamanders that were black and red and some were green. Mostly they looked like regular lizards.”

Clearly, people like the Redenbaughs appreciate the Hollow. But Local officials also express warm sentiments.

“Lincoln Borough is very proud of the conservation of Dead Man’s Hollow,” said Ronald Rosche, past borough president and councilman for 17 years. “It’s something that should be done everywhere. Saving these properties now–while there are still some left–is something that is going to be needed down the road as a place where people can go and be quiet and enjoy nature.”